A Better Equipped Toolbox

The Disciplined Entrepreneurship Toolbox is a set of tools and checklists that helps you build a healthy and successful startup based on the 24-steps process created by Bill Aulet, and explained in the book and workbook with the same name.

We created this toolbox five years ago and it has since helped more than 20,000 founders, accelerators, investors, students, and educators.

When it comes to entrepreneurship, one of the main things we try to teach (and learn ourselves), is that there is no “one recipe” for success and that in order to grow, as healthy as possible, you must keep a close eye on the needs of the users or the changes in the market and improve your product accordingly.

Which is why, earlier this year, we launched an updated version of the website with three new key features that help educators guide startups in the right direction.

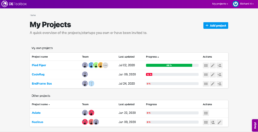

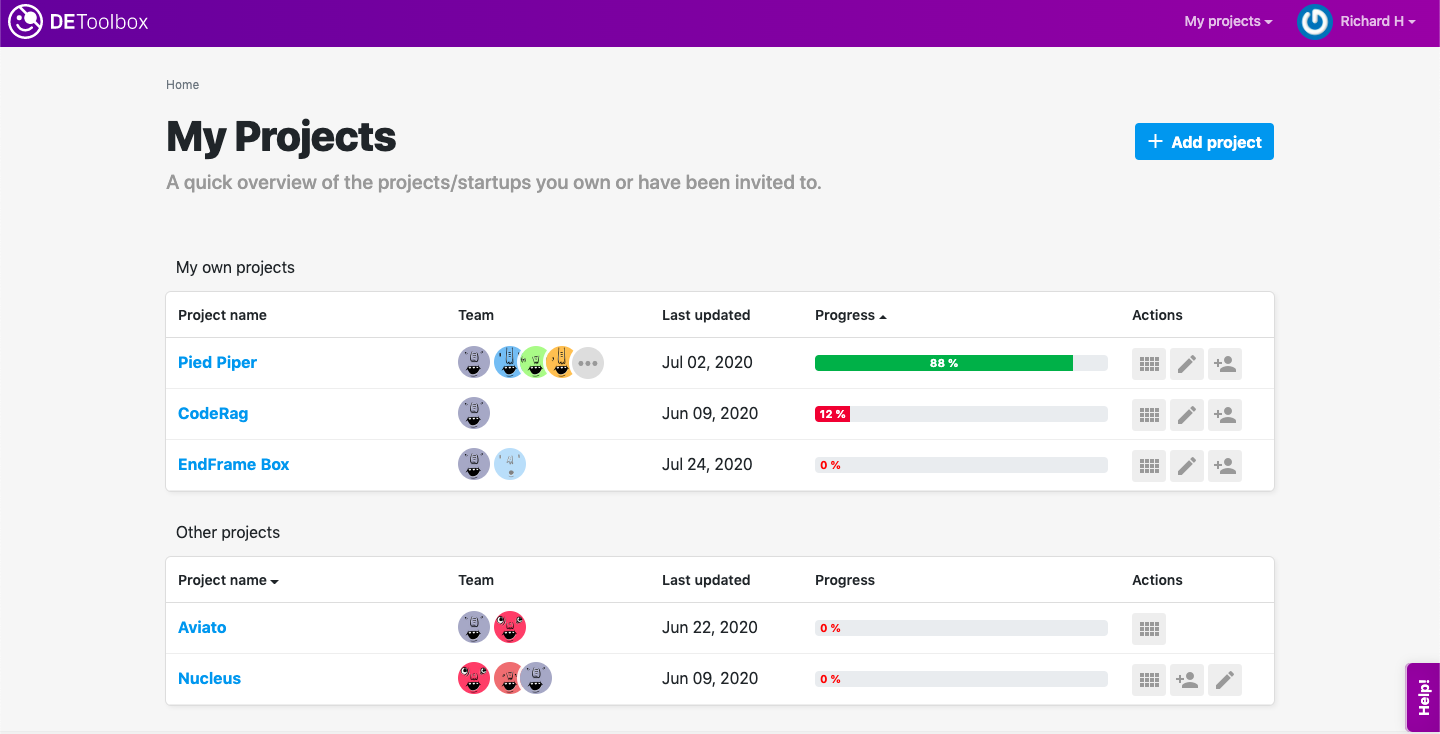

Seamless tracking

We’ve improved the way you track the progress of your startups. In the new dashboard you can now oversee overall progress in a straightforward, visual representation, see how engaged the founders are by checking when the project was last updated, and you can add new team members to each project. The step progress is now calculated differently to give you a more realistic view of what is actually happening and it is based solely on the deliverables, which are the conclusions added at each step.

All of these come in handy especially when juggling with multiple projects or startups. It helps you understand who is moving forward and who still needs help or a slight push. You can also observe the dynamics of your cohort and how invested they are in becoming disciplined entrepreneurs.

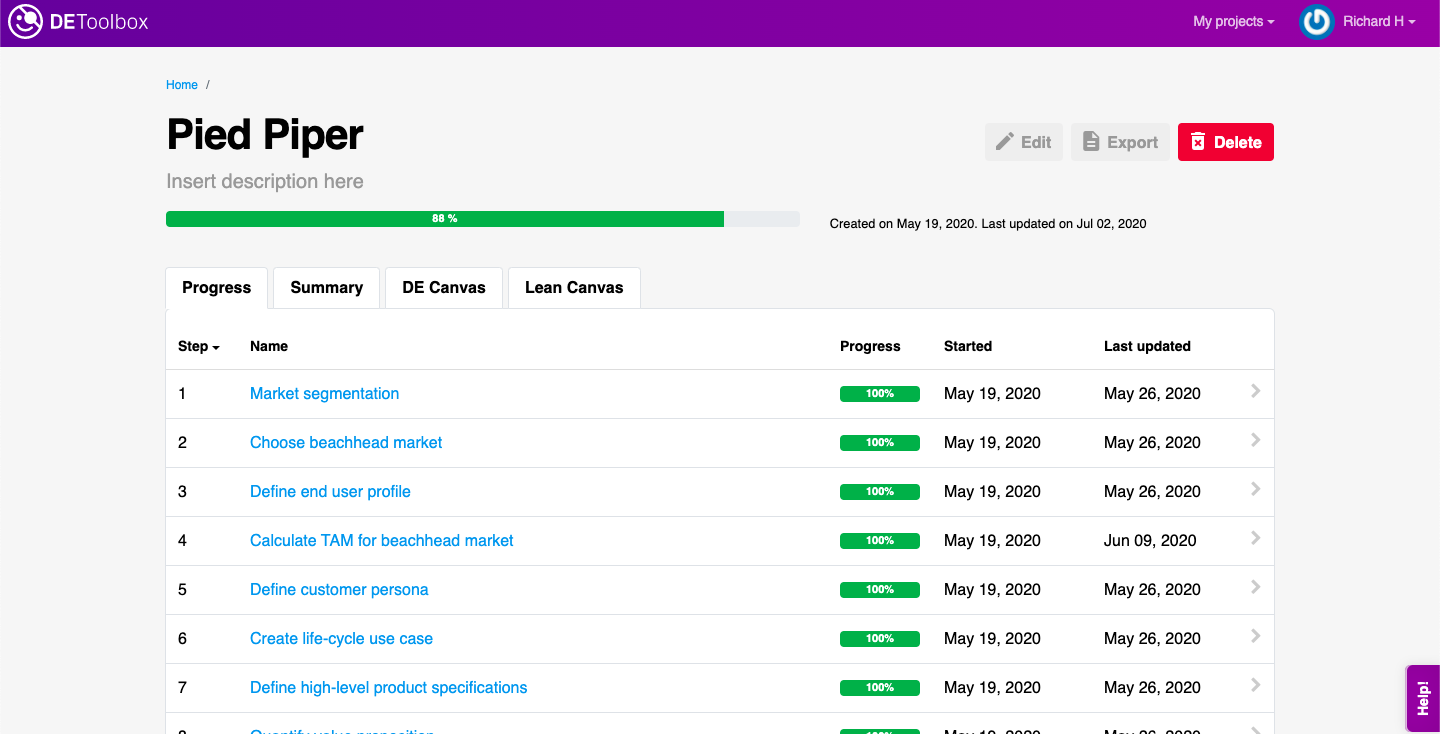

Project-level view

Looking at things on a more granular level, the details of what each founder/student is working on are present inside each project’s dashboard. There is a progress bar for each step individually, as well as a timeframe on when it was started and last updated. All of their conclusions are laid out in the summary tab and can be exported. In the near future, we’ll add two more canvases to view the work (the Disciplined Entrepreneurship Canvas and the Lean Canvas).

We don’t let founders dive in blindfolded, so a set of instructions is provided on each step to help them understand better what they need to work on and where their focus should lie. We’ve also written a few articles that help them build a persona, define their problem statement and how to research for funding, complete with downloadable templates to help them in the journey.

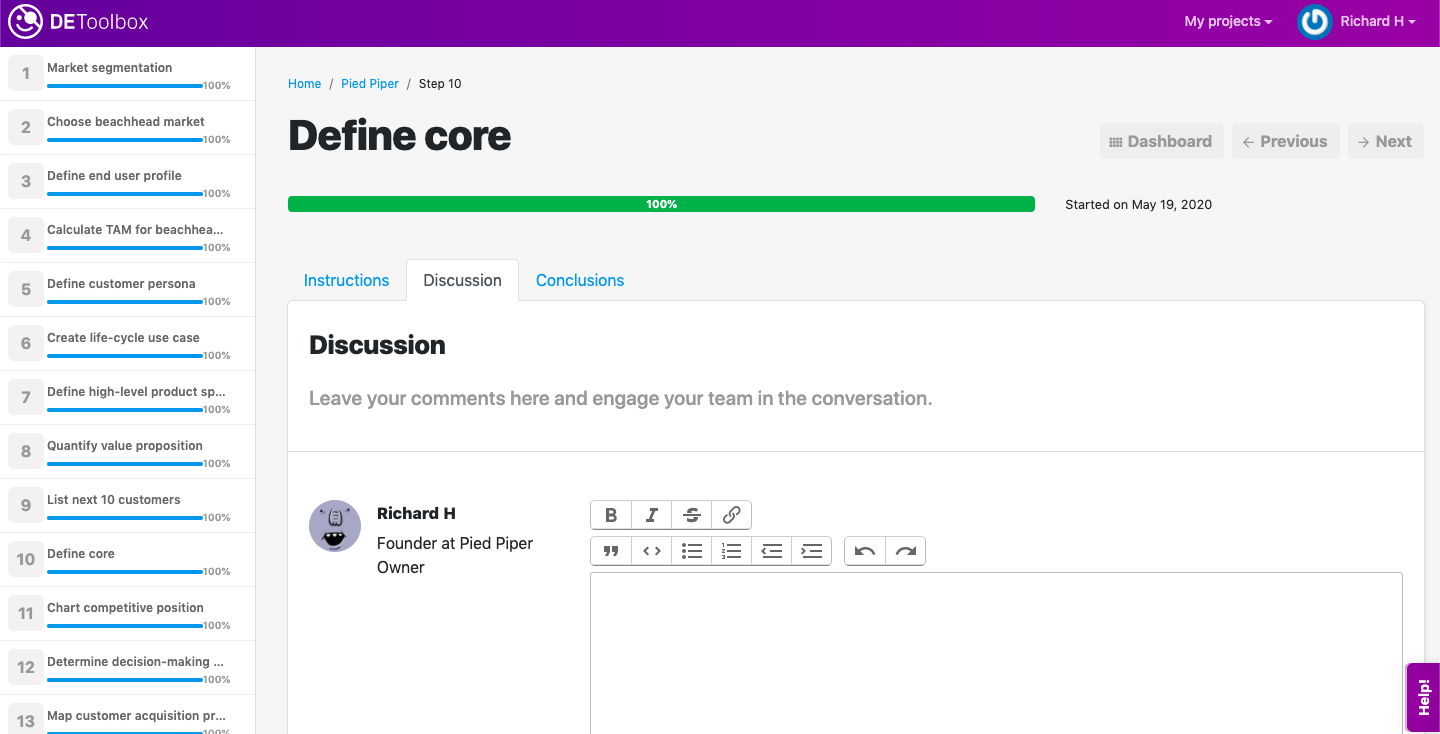

Discussions

Navigating the waters of entrepreneurship isn’t always easy, and having people in your corner, helping you steer the ship in the right direction goes a long way. On our platform you can assign mentors to each team to help them go through every step of the process and, in this updated version, we’ve transformed the feedback option into a discussion board.

We realised that communication should be two-sided and that feedback is truly valuable when it is put in context and met with follow-up questions. The back and forth between colleagues, educators, mentors, advisors and any other people involved in each project helps refine each conclusion. The discussions are held at each step, as keeping the main focus on each individual step and the work around it is essential.

As educators, we are only as good as the entrepreneurs that we help shape. Our platform is built to give the founders the necessary tools to survive in the wilderness that the startup land is, the educators a structure for sharing knowledge and early-stage investors a way to base their decision more on facts and less on gut feeling. All the other features that have proved to be very useful in overseeing and helping with the startup journey, such as exporting data, sorting through startups based on progress, team collaboration and others, are still available on the platform and we are currently working on releasing new features. The journey is never complete.

Why not book a demo with one of us at the Disciplined Entrepreneurship Toolbox and see for yourself?

Building a Bulletproof Startup: Business Model Canvas vs Lean Startup vs Disciplined Entrepreneurship

Startup is a word that gets tossed around a lot and its definition takes on many forms. It’s a state of mind, a disruptive business, a new budding venture, and many other things. Yet there are no set of rules to the game, no magic recipe for success, nor scientific approaches, in spite of all the thousands of books and gurus (including us ?) that address this topic. That’s why we’ve decided to take a deeper look at the most popular and widespread approaches to building innovative companies.

Startups are anything but traditional businesses

First, let’s do a brief comparison of how building a startup is different from building a traditional business.

Growth vs Scalability

Typical brick and mortar businesses usually aim for steady revenue. They think about the best ways to get and maximise profit. To grow, they have to hire new people and get new resources, which makes the growth stable and linear. You’ll rarely see exponential growth in their case.

The startup approach is a bit different. Most startups rely on building technology products. Which means that growth is not proportional to the number of employees or physical resources. Scalability is almost always top-of-mind, that’s why everyone dreams of becoming a unicorn in the startup world.

Existing markets vs disruption

Think travel agencies vs Airbnb, taxis vs Uber, television vs Netflix. Traditional businesses usually tap into existing markets and have a myriad of examples to follow. Customers are already familiar with the types of products and services they provide.

Startups want to make a splash in these markets. Their purpose is to improve parts of the day to day activities that we didn’t even know need improvement. But walking on roads that others haven't walked before is dangerous, and most startups die on the way.

Dealing with uncertainty

This is the cause of death for most startups. The old business school approach to starting a venture requires you to create a business plan and jot down the first 3 to 5 years of your company’s life. Which is fine for traditional businesses. Where you can benefit from other people’s experience and knowledge, and use it to envision the company’s life.

Not so much when you’re trying to innovate. The traditional business plan is static and when applied to startups it provides no real way to measure ROI and financial projections. Eric Ries, probably the most famous theorist in the startup world gives the best definition of a startup. Ever (in my humble opinion):

“A startup is a human institution designed to create a new product or service under conditions of extreme uncertainty.”

Eric Ries, Lean Startup.

Searching for sanity

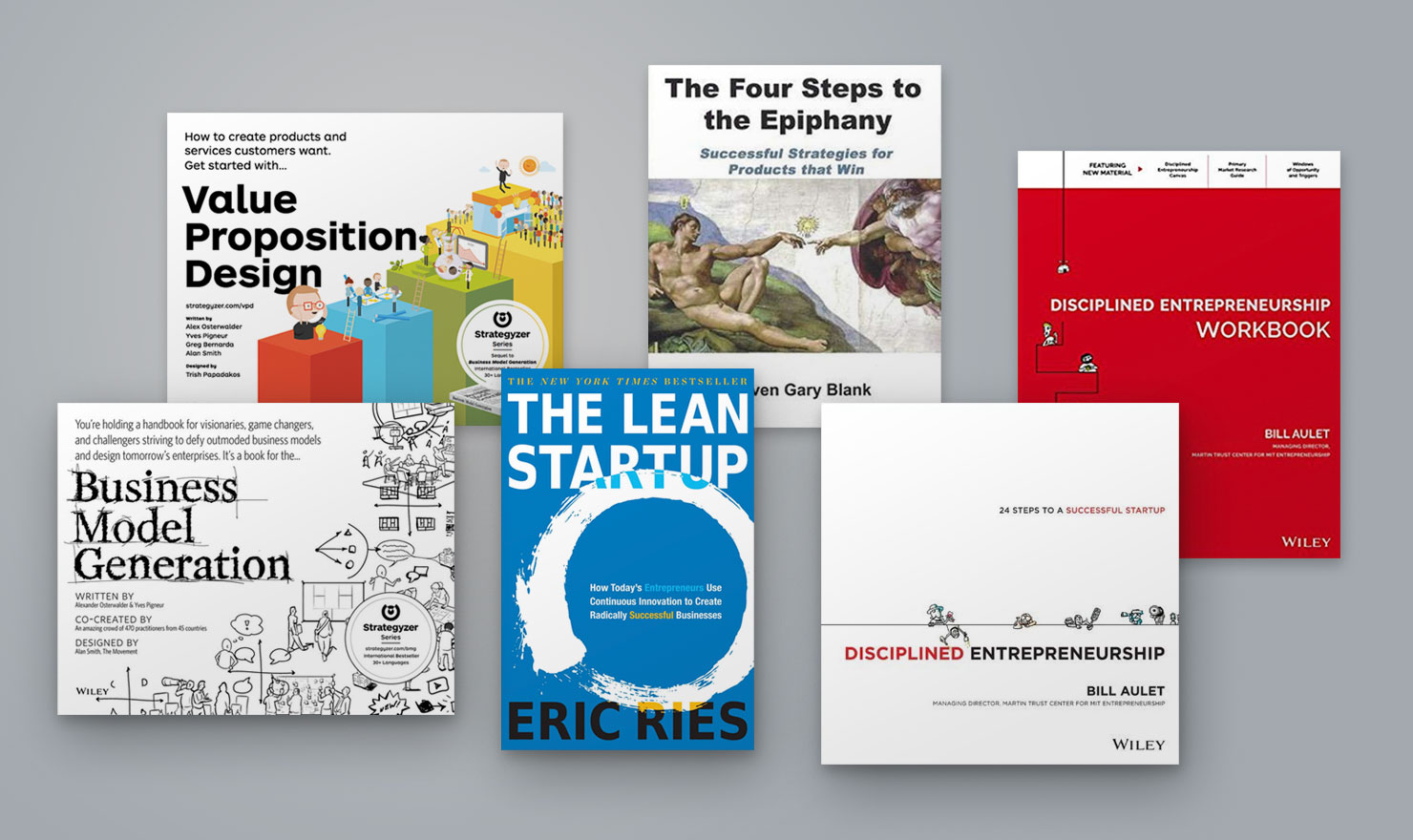

All these differences make startup building a rather adventurous and unsuccessful activity. Luckily, in the past decade, frameworks that are more tailored for startup’s specific needs, have emerged. Among them, the most popular ones are:

- Business Model Canvas (2010) created by Alexander Osterwalder and Yves Pigneur.

- Lean Startup (2011), coined by Eric Ries based on lean manufacturing and Steve Blank’s “Customer Development Model”.

- Disciplined Entrepreneurship (2013), developed by Bill Aulet based on his experience nurturing startups out of MIT for more than 9 years.

Each one of these methodologies was created with flexibility in mind. They provide a solution for the uncertain nature of innovation-driven enterprises, solving a lot of problems. Through them, you’re encouraged to test. Iterate. Adjust. You build your company knowing real market needs, based on feedback and in-depth research. They expose a much clearer path to success, long needed in a sector where uncertainty is often the only certainty.

Each one of these methodologies was created with flexibility in mind. They provide a solution for the uncertain nature of innovation-driven enterprises, solving a lot of problems. Through them, you’re encouraged to test. Iterate. Adjust. You build your company knowing real market needs, based on feedback and in-depth research. They expose a much clearer path to success, long needed in a sector where uncertainty is often the only certainty.

Tools for the real world

These startup frameworks seem great when you read the books or attend the courses. In real life, things are very different from the precise process in the books. I've seen it mentoring and advising hundreds of startups, accelerators, and incubators, in US, Europe, Asia, Oceania. Everywhere.

The newness of these frameworks means we don’t have enough data to tell whether they’re efficient or not. The percentage of startups failing still goes as high as 90%. Is it because of existing flaws in these methodologies or just human nature? Unlike religions, there is little room for one startup bible. And I’ve found out that blindly following only one of these methodologies creates exposure to their flaws and increases the risk of fragility.

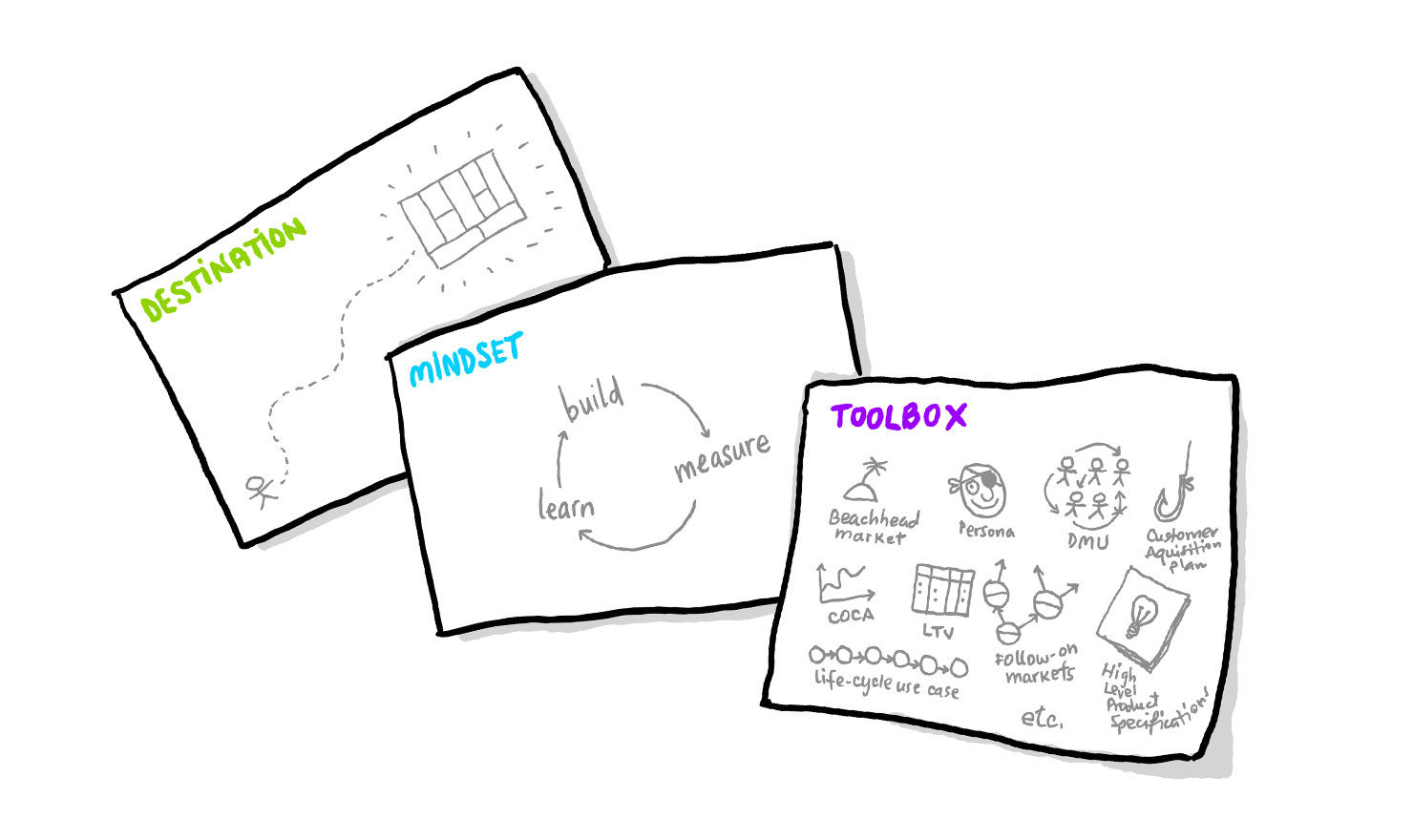

In my view, the startup journey resembles the journey of explorers to uncharted territories or the Gold Rush to the American Wild West. These explorers had little use for Bibles (except for psychological comfort, maybe) but in great need of maps, tools, and new mental models. Thus, my analysis looks at how these startup frameworks fare at this.

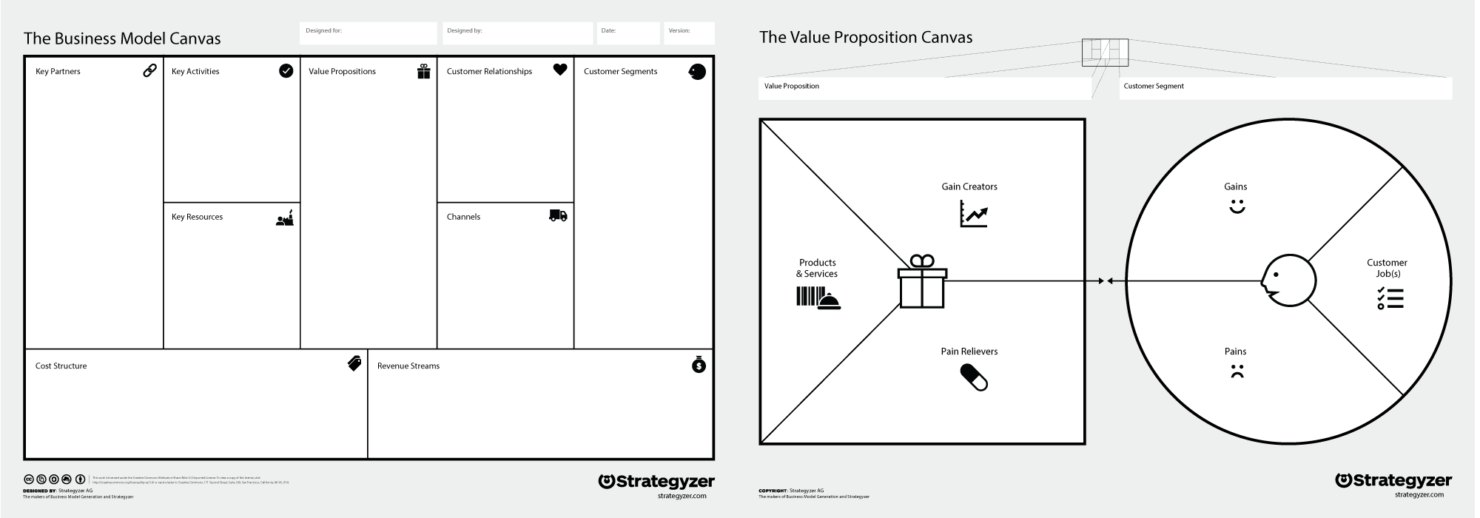

Business Model Canvas

The Business Model Canvas is a chart that allows you to create a more visual representation of what the business should look like. It maps out key features, the product design and, once completed, it tells you the exact key points that you need to address when building your company. The Value Proposition Canvas comes as a follow-up but is an integral part of the process as it helps you understand your customer first and how you can create value for them.

“The same products, services or technologies can fail or succeed depending on the business model you choose. Exploring the possibilities is critical to finding a successful business model. Settling on first ideas risks the possibility of missing potential that can only be discovered by prototyping and testing different alternatives.”

Alex Osterwalder, creator of the Business Model Canvas.

Pros

- Provides a visual, easy to understand overview of how the company will look and how it creates, delivers, and captures value in relation with the customers. People at various levels of the organization can share the same vision and mission. It’s easy to understand even for people without any business experience or education.

- Focuses on how the value flows throughout the business regardless of the stage of development, the business offering, or the intricate details of strategy implementation. This helps to “keep the main thing the main thing” (i.e. focus on important aspects) when reviewing any decisions that impact the business.

- Through the Value Proposition Canvas, it helps with understanding the customer beyond simple marketing parameters. It tries to create empathy for the users to help the business owners understand the core value of what they are building.

Cons

- It’s a map of the destination, but with no compass or specific tips on how to get from point A to point B. There is also little information on how to validate if the destination is feasible, especially for startups dealing with uncertainty)

- It has a fixed architecture (nine building blocks that need filling in) which may be less clear or relevant to tech startups. In their case, a deep understanding of the relationship might not be as relevant in early stages. Key activities are somewhat redundant with key resources. Ash Maurya has adapted this to a much better version for startups, the Lean Canvas.

- Being very minimal, it can give a false impression to beginner entrepreneurs that “they have it all figured out”. As a result, they jump into building their product or solution—similar with taking a map for good and putting all your efforts into walking towards the presumptive destination.

Lean Startup

Lean Startup is a methodology that encourages you to always ask and never assume. To push forward your minimum viable product, to test things and adjust as required, and to keep your user at the center of it all. The Build—Measure—Learn feedback loop is a core component of this framework. It emphasizes more on having the right attitude and mentality, rather than what steps need taking.

“The ability to learn faster from customers is the essential competitive advantage that startups must possess .”

Eric Ries, The Lean Startup: How Today's Entrepreneurs Use Continuous Innovation to Create Radically Successful Businesses

Pros

- The framework provides the right mindset for entrepreneurs to deal with uncertainty. It focuses on experimentation through defining assumptions, testing them, then iterating their approach (the build-measure-learn cycles).

- Focus directed at user/customer in the customer discovery and customer development stages.

- Introduces important concepts as Minimum Viable Products and pivoting. These concepts are counterintuitive (if not outrageous) for someone with a traditional business, where success is often a result of marginal improvements and persistence.

Cons

- By promoting “accountability through learning” as a concept without a clear discipline or guidelines on how to implement it, it gives entrepreneurs a false illusion of progress through failure. A startup should not be an educational opportunity first, and learning should be a byproduct of the journey, not the main goal.

- It encourages focus on product vs business (build/measure/learn). Although Ries gives good examples of the MVP and pivoting criteria, these concepts are mostly applied by founders as an excuse to stay in the comfortable zone of building products or technologies, after only a superficial understanding of customers. The lean management process is effective in a more mature company (Ries took and expanded on the lean manufacturing perfected by Toyota) but presents higher risks for startup teams. In more mature markets or deep tech, MVPs need a lot of time and resources to build. To keep with our explorers' metaphor, it’s like giving them the mind and heart of an explorer, but then letting them wander around forever. Getting them excited about the travel and views, but with no understanding of the destination, or the perils and strategies of the journey.

- While the mindset and examples are spot-on, the process leaves a lot of room for founders to avoid hard questions and take the wrong approach. The Lean Startup philosophy asks to identify assumptions first, then set clear metrics for validating them, and only last to define and build the experiment. But in real life things happen the opposite way. If you know any lean entrepreneurs, more often than not they would get excited about a product feature, then choose a metric based on what they build, and only then try to link it to an assumption—to “comply” with the lean label. It is is not a flaw of concept, but of implementation. Luckily, in his Running Lean book, Ash Maurya presents a better process of how to implement a lean mindset. Maurya presents a better process of how to implement a lean mindset. The only thing to remember is that, same as in physics, experiments can only invalidate most hypotheses. But where do we find those founders who are willing to try to kill their “baby” to be successful?

Disciplined Entrepreneurship

Disciplined Entrepreneurship is a structured approach that guides the starting entrepreneur through specific actions that need to be taken before jumping into developing the product or service. This methodology shows how innovation-driven entrepreneurship can be broken down into discreet behaviors and processes which can be taught in just 24 steps.

“The single necessary and sufficient condition for a startup to succeed is a paying customer”

Bill Aulet, MIT Sloan Professor, Disciplined Entrepreneurship author

The methodology introduces to the startup world useful concepts such as beachhead markets, personas, high-level product specifications, quantifying value, decision-making units and many more. They are not only presented in an easy to understand way but are linked with the author’s experience as a serial entrepreneur and highly adapted to tech innovation.

Pros

- The focus is on the business side of a startup (customer segmentation, use cases, pricing strategy, decision-making on customer side etc.). Through it you identify potential customers, research their pain points and the sales process. It contains most aspects of the Business Model Canvas but goes more in depth for a proper understanding. This methodology overlaps with the Lean Canvas approach in identifying and testing key assumptions—but with the purpose of building a Minimum Viable Business Product, that will prove not only that the solution is usable, but that it can generate revenue.

- It is a clear and detailed map of the territory from the first step to the last one. It goes very in-depth with details, which is useful for people with no previous business experience or degrees.

- It’s based on Aulet’s personal experience and his work with hundreds of innovative startups out of MIT. Focuses on numbers and process to reduce uncertainty and keep people on the right track.

Cons

- Being taught in educational contexts, the steps metaphor gives the false impression of a linear process. Real life is more chaotic. While Aulet explains in the book and the visual representation of the framework that it is iterative, most founders feel lost after they’ve reached step 22, where they find out that their assumptions were wrong and need to go back to square (or step) 1.

- Requires a lot of effort in dealing with multiple unknown business variables before getting to the enjoyable part of the process (building the product or technology only starts towards the end of the process). This makes it very likely for founders to quit figuring out all the details. The fact that “It takes months but may save years” (as I often tell founders I work with) doesn’t make it very appealing. I usually recommend founders to go through the whole 24 steps with their team in one day (to have a superficial but 360-degree view of their startup). After that to go in depth over the next week. And, finally, focus on the areas that are most relevant to their situation.

- It focuses on the path on the map and the tools in your backpack, not on how to be an explorer or the clarity of the destination. That creates the risk of short-sightedness. This is fixed with the new concepts and the Disciplined Entrepreneurship Canvas in the sequel workbook.

And now what?

An in-depth overview of the methodologies reveals a hidden truth: none of them is universally valid. As I said, there is no one Startup Bible that guarantees redemption from uncertainty and the perilous journey. Each of them focuses on very different aspects of a startup. Using them together, as different tools and toolboxes in the arsenal of an entrepreneur, is the best approach to building a successful venture. Instead of choosing one and hope for the best possible outcome, I would recommend combining them.

Start planning your journey by using the Business Model Canvas or the Lean Canvas. Understand your destination before anything else, and your motivation (because that is what is going to keep you and your team together on the path when things get hard). A moonshot or North Star is more important than anything. But then what matters are the first steps.

Start planning your journey by using the Business Model Canvas or the Lean Canvas. Understand your destination before anything else, and your motivation (because that is what is going to keep you and your team together on the path when things get hard). A moonshot or North Star is more important than anything. But then what matters are the first steps.

Understand how Lean Startup works, how to start discovering customers. Get out of the building and talk to them, no framework or toolbox is going to replace that. Create the profile of your persona using the structured framework Disciplined Entrepreneurship provides. Get to know your customer. Your beachhead market. Your TAM (what?). The information that results from following the first steps of this framework is more detailed and provides more insights into user/client needs and it will make it easier for you to work with the Value Proposition Canvas or the empathy maps from Ideo.

Use our Problem Statement Canvas to understand the problem without considering any solutions. Then go back and adjust the nine blocks of the Business Model Canvas. Then go more in-depth, trying to go to the level of detail in the Disciplined Entrepreneurship Canvas, by going through the steps of the framework. Don’t start building the product yet, we know you have that itch. Get to understand your assumptions first, only then define the metrics and experiments, based on the Running Lean process, which is the best implementation manual for the Lean Startup philosophy. Don’t build an app when you can build a landing page, or Powerpoint, or Kickstarter campaign. Don’t build an AI if someone in your team can do it using email and a spreadsheet. Have them pretend they are THE chatbot to validate it’s a business first before you start writing code.

Make small improvements based on user feedback, not on your grandiose vision (you’re not Steve Jobs or Elon Musk, although you could be better). But don’t focus just on the product. Building a business is much more important and people often overlook that. And don’t spend time listening to the advice of mentors, authors or gurus (like us)—instead, listen to your customers. Then do it again.

Startups are all about the unknown. And flexibility. And testing. There is no one right formula for becoming successful and any entrepreneur looking to start an innovation-driven enterprise should know in advance that fixating on one tool to solve all problems is rarely the answer. You wouldn’t leave on an expedition taking only one thing with you (as long as it’s not a spiritual or religious one), so don’t be a blind follower or zealot of any startup trend.

Think for yourself and choose your tools wisely, because your journey is unique.

Redefining Entrepreneurship: Five Questions

Republished from How To Web

If you want to learn more about entrepreneurship, Marius Ursache is the first person you should ask. His vast experience in this field comes from being a co-founder of four companies. Starting with Grapefruit and finishing up with Metabeta, Marius Ursache is nowhere near settling down to a regular job. Being an entrepreneur is a passion for him, and that is why he likes to share his thoughts on the matter at MIT where he is a Mentor and Teaching Fellow.

Marius Ursache is also going to be a speaker at the How to Web Conference this November. We asked him to share only a few things with us in this interview and to leave the good stuff for the Conference. Let’s see what entrepreneurship is all about.

How would you define an entrepreneur? What makes one more of an entrepreneur: the mindset, the skill set, or the network?How do you see entrepreneurship: more like a sprint or more like a marathon?

I don’t believe in recipes—not even in the kitchen since I love cooking (maybe this is the reason why my baking experiments are anything but edible). I believe that we (humans) are changing, evolving, slowing down, shifting focus, falling in love, obsessing over some things while completely ignoring other more important ones. There is no clear boundary for when you become “more of an entrepreneur.”

All three things are essential: mindset, skill set, network. I would add passion, anger, talent, obsession, empathy, pragmatism, a pinch of delusion and a great deal of luck.

I don’t believe in boxes either. Putting things in boxes gives people the illusion of understanding something that is too complex for our limited brains. So, if you want to put the entrepreneurial journey in some boxes, it will look like a sprint at times, like a marathon other times, like wrestling on Fridays, like weight-lifting when you miss deadlines, maybe like yoga if you read that meditating 5 minutes a day with an app makes you a better entrepreneur. It looks like a boring never-ending chaos most of the time.

What are some of the processes an early-stage entrepreneur should apply strictly? Can you please detail from a business point of view and from a management point of view?

You know that annoying answer, “it depends”? It applies here too. Nobody figured out the magic sauce yet—otherwise, they would be relaxing on a tropical island, instead of writing business books.

Instead, here are some things that work for me. They won’t make you successful, but what I will say is that whenever I don’t apply these principles, I get burned or suffer a significant setback.

Sleep! For a few years, I was involved in four different companies, one NGO, teaching and mentoring in two major international programs, all these while traveling. I felt I was losing my mind whenever I was not sleeping properly. The radical shift in productivity and well being came when I finally understood that energy management is a lot more important than time management.

Be disciplined! Many of my friends will describe me as a robot or control freak who has all his life planned in Trello or a spreadsheet. I wish I were that disciplined. For me, discipline is not an extrinsic constriction, but rather a trait that allows me to do whatever I want to do, whenever I want to do it, not when my calendar lets me. Discipline is not about getting out at 5 AM and running for 10Km, but rather about making sure that I have a plan for what I am doing, instead of spending my life on a to-do list created usually by others (clients, colleagues, suppliers, friends, etc.).

Don’t work with assholes! Life is too short, and this rule fires back with no exception. Remember this next time when you get burned, after working with an asshole and hoping that the money you get makes it worth.

Be nice! Duh! Your mom told you that, too!

Once a startup starts to grow, the entrepreneur becomes less of an innovator, and more of a manager/businessman. Would you agree on that? What’s your take on this?

There are three hats: the handyman, the manager, and the entrepreneur—here I am putting people in boxes, I hate myself now! (Nah, not really, I am just quoting Michael E. Gerber).

In many cases, the startup journey requires you to wear more the handyman hat (you don’t have the money to pay other people to do it), and you’re more a janitor (you have to clean up all the mess) than the CEO title in your pitch deck or your secret belief that you’re a real entrepreneur. Later on (hopefully), you get some revenue (don’t laugh if you’re a business owner, in tech startups revenue is an odd occurrence), then you hire other people so you can be a real CEO.

Now, you finally have a team but have to manage people and also do their work (because your revenue is not that big for you to hire the best experts—they’re going to big outsourcing corporations where they get paid double). Let’s say you’re fortunate and finally get to a nicer revenue, hire better people and get over your OCD on their work. You realize you have no idea what management really is, then you start reading books about Management 2.0, Recruitment 3.0 and Operations 4.0. Nothing makes real sense (if you’re lucky you don’t have to go through an MBA for that), and what makes sense seems like common sense, but it’s unpredictable.

After struggling with this for a while, you end up either becoming a better manager or getting used to being the same mediocre one over and over. Entrepreneurial mindset and innovation are a concern when you give interviews, but not really on your to-do list when paying salaries and keeping your investors happy are what makes you twitch.

Management is about predictability, while entrepreneurship is about the unknown. So to become the visionary entrepreneur again, you have to stop working in the business and start working on the business (from the outside). Which is hard because you’re in permanent conflict with the person who’s managing the company, because you want to friggin’ change everything that’s working now, spend the hard earned money on some stupid experiments, without any commitment, accountability or anything than the gut feeling to support your “innovative and disruptive vision.” I don’t know about others, but this was my journey.

Are there any changes regarding processes applied after a startup becomes an established company? If yes, what changes and what is the impact?

As a startup, you think you know what you’re doing. You’re wrong (I don’t need to prove that, the future will). What you have is a fuzzy dream, and most of everything (processes, people, products, even vision) will change every few months. There is no point in creating procedures for everything. What is critical is the ability to work as fast as possible and break as many assumptions as possible (yes, exactly Facebook’s “Move fast. Break things” mantra). As a startup, it’s better to optimize for optionality: be flexible and adaptable.

As a revenue-generating company, you want predictability of your revenue and your growth. This is why you start putting in processes. I try to put procedures in place only when they are useful for a team, and they bring a definite improvement. Not to create a rigid box of “this is how we do stuff here” which ends up creating a culture that will attract nobody really smart.

Regarding work-life balance, is there any difference between working for a startup and working for a large company? Most people live with the idea that a startup means more freedom, more fun, etc. Is this a myth or a reality?

There is a joke saying “Entrepreneurs are people to quit working for 40 hours per week so that they can work for 80 hours per week”. It’s not a joke, it’s reality before you learn how to manage being an entrepreneur.

Work is an essential part of life for me. I don’t really like people who can’t wait to retire, but I’ve come to accept that they might have different wishes, mindsets and personal priorities which makes retirement an attractive concept.

Even in their case, I think the whole work-life balance debate is bullshit. We have to make some choices in life (usually having to choose three items from this or a longer list: career, family, friends, hobbies, health) and nobody usually forces us to choose a career instead of family or friends. It’s our inability to manage the consequences of our choices that creates the drama and complaints.

And if you’re complaining about it, think of this: if you really-really-really want something in your life, you will find a way to do it eventually.

That’s why I don’t play guitar in a famous rock band. Instead, I’m giving interviews like this one (I really-really-really love to give stupid advice which some people might accidentally take as useful).

You can book your How to Web Conference ticket to discover, learn, and build the future.

The Best Fundraising Option for Disciplined Entrepreneurs

As an entrepreneur, we should first be very good at finding the right problem, before spending weeks, months or even years building solutions. Sometimes, despite the fact our solutions are amazing technologies or superbly-written code, they fail because they don’t respond to real market needs. We only come to this realization after having built a product that doesn’t sell.

We can tackle this by doing thorough customer discovery, by building MVPs or by planning carefully. Yet we keep failing, getting up, trying again, and failing again. We apply all the advice from all the startup gurus, and yet we keep failing until we run out of cash or become too tired and give up.

But what if you could sell your product before it even existed?

Validating customer needs

The fear of selling something that doesn’t exist is understandable, but you can start this process during your Primary Market Research. Every interview with potential customers can be a chance for you to measure their real interest. It gives you an opportunity to re-think, test, refine your solution and prove your business model.

One of the fallacies of the Lean Startup methodology and building MVPs (Minimum Viable Products) is that these MVPs don’t really prove there is a real need that will drive customers to pay. A startup should be a business, not a product or technology, therefore, experiments and hypothesis should be linked to the viability of the business, not of the product of technology. This is why a better approach is starting with an MVBP (Minimum Viable Business Product), which can validate the need from a commercial side (not a technology side).

This is what Dropbox did when they designed their product 11 years ago. Instead of taking the “build it and they will come” approach that was expected from them as engineers, the team gathered feedback from customers about what really mattered to them, in parallel with their product development efforts. In trying to answer the question of whether or not people will try their product because of the superior customer experience it provided, they confirmed that file synchronization was a problem that most people didn’t know they had. Their interactions with customers who experienced the solution for the first time showed that people couldn’t imagine ever having lived without Dropbox.

The original Dropbox video, narrated by Drew Houston, Dropbox CEO

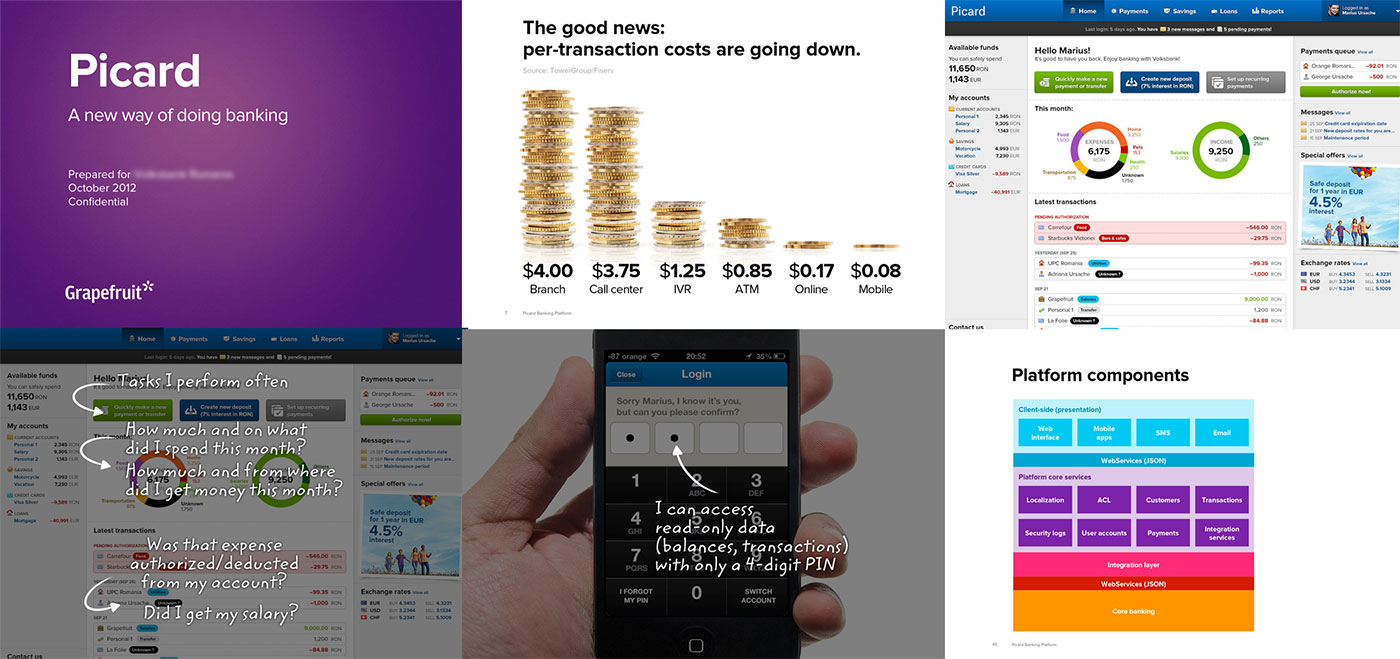

The High-Level Product Specification

The Disciplined Entrepreneurship framework, created by Bill Aulet at MIT, startup teams are encouraged to create a presentation of their solution, which we refer to as a High-Level Product Specification. It can be a PowerPoint presentation, a short video, a drawing, an illustration, a landing page, a storyboard, a diagram, or even a sketch on a napkin. It can be anything that explains what your solution is and how it solves the customer pain.

Being a representation of what your product will be when it is finally developed based on what you know at this point in the process, the High-Level Product Specification has multiple benefits:

- Brings the whole team on the same page in terms of what you’re building, how it looks, and how it works.

- Allows receiving unbiased feedback from potential customers.

- Can help you get funded without giving away any equity.

The first two benefits are pretty obvious, but I’d like to focus more on the third benefit, which is often overlooked as a financing option.

The buzz around the Silicon Valley tech industry has created a mythical path that seems a prerogative of any successful tech startup:

have idea → build MVP → raise VC money → build free product for everyone → tadaaa

For the past five years, I’ve consulted accelerators and investors, coached and advised hundreds of startups around the world. Many of the founders I meet and talk to have the above misconception, which is in more cases the cause of their startup’s demise. Everyone dreams of being a unicorn today, but few are the ones who care about revenue.

However, a well-made High-Level Product Specification can help you follow a different path, one which has more odds of success for the majority of startups. Customer funding is rarely praised by startup media, often overlooked as a financing option when it’s actually the best choice for most startups. Having access to funding while validating a real market need, getting real-time customer feedback and not having to give away equity—can it get better than this? If customers are willing to pay for your solution before you build it, it not only offers you the cash to build it but help you build a viable business product.

How to build a High-Level Product Specification

Start with the customer in mind, right? Go back to the people you’ve interviewed for your Primary Market Research. Your first goal is to reach people who fit your ideal customer profile and see how they react to your image of the product.

- Do they understand it?

- Are they grasping the way it would work?

- What are their questions and comments?

- How does this relate to the problem your product aims to solve?

- What benefits do they see in the possibility of this product?

- How would using it change their lives?

Make sure your visual description focuses on the benefits and not the technology or functionality. In particular, focus on the benefits that are related to the user’s top three priorities. Be clear on the value proposition this product has for the end user and don’t get lost in details, you only need enough information to show high-level functionality that will drive the benefits.

Choose the form of your High-Level Product Specification based on your target audience. Younger audiences would react better to a landing page or mobile ad, older or more conservative audiences might be more comfortable with a printed brochure, and busy people could easier watch a 30-second video than flip through a PowerPoint presentation.

Many forget that Oculus Rift, now a Facebook product, was initially crowdfunded, using a “show-don’t-tell” approach based on gaming videos.

In the end, your High-Level Product Specification is what’s going to convince them (or not) to give you money. But for that to happen, you want it to be more than just a walkthrough of the product; you want it to illustrate the problem it’s solving, and how it will achieve that to provide added value.

Using a High-Level Product Specification to get customer funding

B2C startups: Crowdfunding

You’re already familiar with the most popular and successful example of customer funding: Kickstarter successful projects. Since their 2009, they’ve had 14 million people backing projects, $3.6 billion pledged, and 140,330 projects successfully funded. All this using High-Level Product Specifications. Creating a project on Kickstarter requires founders to have “a project page with a video and description that clearly explain the story behind the project.” Raising money can be that simple if you know who you’re creating for and what you’re creating.

Customer financing continues to be one of the best financing options. In fact, Massolution’s crowdfunding statistics show growth increased last year to raise $16.2 billion, a growth of 167% over the prior year and could top $34 billion in 2018. Crowdfunding in North America grew by 145% to nearly $9.46 billion raised, with crowdfunding in Asia surging 320% to $3.4 billion raised. Business & entrepreneurship accounted for nearly half of all money raised.

B2B startups: Customer financing

While this seems to become a standard path for hardware startups, B2B businesses can also benefit from this approach, perhaps even more. Signing 10 letters of intents or actual commitments in your beachhead market can validate your product and get you funding at the same time. This means you’ll be able to finance your product development with revenue from customers who believe in your product and will help you tailor it to their specific needs. Your product will reflect reality and the actual needs of your clients, which is the desired state for any business. Based on the data you collect as your first customers start using the prototype, you’ll be able to prioritize and build on the right features for your product.

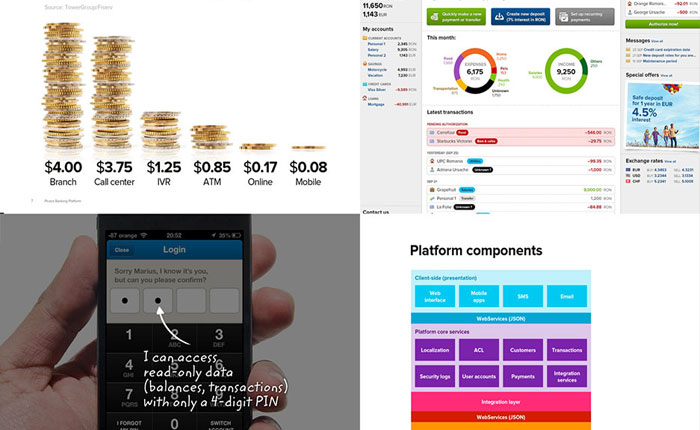

I’ve managed to raised customer funding for several projects in my career—even for a complex mobile banking platform—using only a presentation, also known as “slideware” (a software product that currently exists only as a series of slides in a sales or marketing presentation).

The most popular form of crowdfunding for blockchain-based companies right now is the ICO (Initial Coin Offering). An Initial Coin Offering (ICO) is used by startups to bypass the rigorous and regulated capital-raising process required by venture capitalists or banks. In an ICO campaign, a percentage of the cryptocurrency is sold to early backers of the project in exchange for legal tender or other cryptocurrencies, but usually for Bitcoin. In the early years, pioneer ICOs like Ethereum, Golem Project or SingulardTV raised over 300 million dollars. In 2017, a single ICO, Filecoin, raised 257 million dollars, and a total of $1.6 billion dollars is estimated to have been raised.

Most ICOs use a High-Level Product Specification under the form of a landing page and/or a white paper. Now, while some ICOs are complete scams, with landing pages that are more slidewares than High-Level Product Specifications, I’m talking about the legitimate ICOs. An ICO white paper is a document determining the technology of a blockchain project. It usually contains a detailed description of the system architecture and its interaction with users, as well as current market data and growth anticipations and requirements for the issue and the use of tokens. It also provides a list of project team members, investors, and advisors. Similar to the classical High-Level Product Specification we’ve discussed, the document’s aim is to build trust and describe the product. It contains the problem, the proposed solution, and a description of the token commercialization (product interaction with the economy and technical provisions of commercialization). However, unlike the visual representation I initially described, its main focus is the technology. As ICOs continue to evolve, I think we’ll be seeing more elements of a classical High-Level Product Specification being introduced, for companies looking to make it clear that they’re not a scam and that they do indeed have a real product worth investing in.

By following the previous steps in the Disciplined Entrepreneurship framework, you’ll have the necessary foundation in the form of a clearly defined Beachhead Market, a Total Addressable Market, and an ideal End User Profile. Based on these, your High-Level Product Specification will reflect an actual product, it won’t be “just a slide”.

And this will save you months, or even years, of building a solution that customers won’t pay for.

How to Create a Persona and an End User for Your Startup

One of the hardest lessons you learn as an entrepreneur is to narrow down your options and find focus. Most of us learn this through failure, after chasing too many possibilities at once. From identifying the right problem to solve, to figuring out what your beachhead market is and who your paying customer is, it’s always a struggle to let go.

The currency of modern-day entrepreneurship is ideas. Not an idea but ideas. We’ve talked about this in the context of defining the right problem to solve. Founders have all these ideas about what their product should do and what it should look like, that they lose focus on what they’re trying to accomplish with it. When you ask them “Who will buy this product?” you’ll also get a multitude of ideas, usually starting with “millennials” or “women aged 25–35”. These “customer goggles” make founders see potential customers everywhere they look. Narrowing down their own ideas is not something most people can do. This is where a mentor comes in really handy. As it’s been my experience, having someone who already went through this process (several times) and has helped other founders filter their ideas will make the process so much easier.

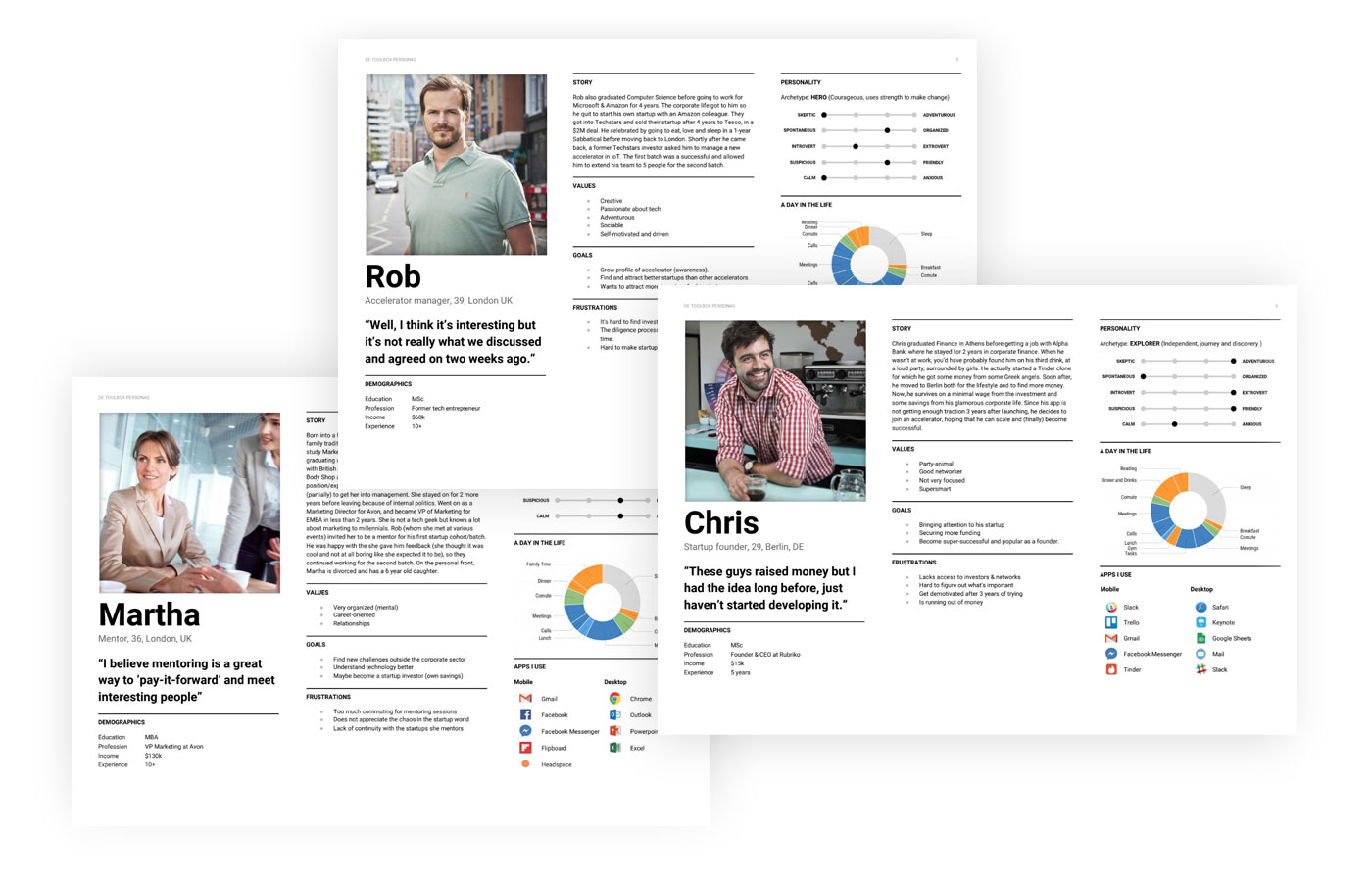

Founders who choose to map their startup building process on the Disciplined Entrepreneurship framework developed by Bill Aulet, Managing Director of the Martin Trust Center for MIT Entrepreneurship start off by creating an end user profile.

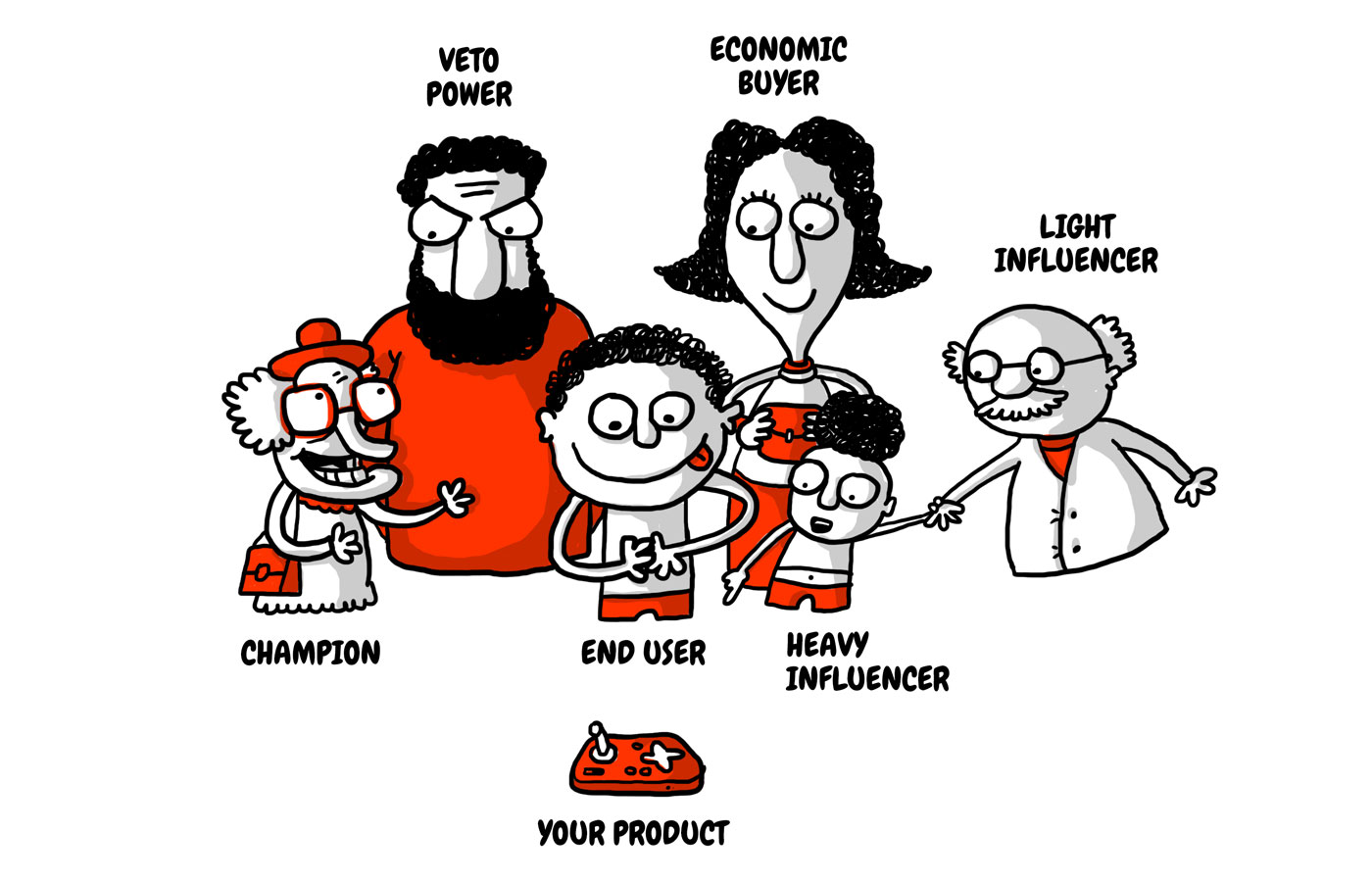

An end user is a person who will be using the product or service. Sometimes the same person will play the role of the economic buyer, but that is not always the case. The Decision-Making Unit can be quite complex depending on the market you address. In B2B the end user is usually the employee using the new tool, while the compliance officer will be the IT manager and the economic buyer the Finance Manager.

Ensuring that entrepreneurs thoroughly research their end user is a step you never want to skip. If founders don’t take the time to fully understand who will be benefiting from their product or service, how their new idea will be used and what those people are like in day-to-day life, you run the risk of having them create something no one will buy (or invest in). A less fortunate example of this is Juicero, ‘America’s favorite $400 juice machine’ that came to a tragic end in 2017 after raising more than $118 million in funding from prominent VCs like Google Ventures and Kleiner Perkins. If you can squeeze the juice bag with your bare hands faster than the machine, why would you buy an expensive device to fulfil the task?

Ensuring that entrepreneurs thoroughly research their end user is a step you never want to skip. If founders don’t take the time to fully understand who will be benefiting from their product or service, how their new idea will be used and what those people are like in day-to-day life, you run the risk of having them create something no one will buy (or invest in). A less fortunate example of this is Juicero, ‘America’s favorite $400 juice machine’ that came to a tragic end in 2017 after raising more than $118 million in funding from prominent VCs like Google Ventures and Kleiner Perkins. If you can squeeze the juice bag with your bare hands faster than the machine, why would you buy an expensive device to fulfil the task?

How to create an end user profile?

1. What problem are you solving?

Start with the problem definition framework, where you guide founders to re-frame their idea into a real problem, rather than a solution. A problem is not the lack of a solution. It is a pain that affects the lives of a significant number of people, who would pay money to have it fixed.

As a founder, what you want is not important. Did you start your company with the solution as the center of it and customers rotating around it? Invert that. Start viewing the customer as the hub and the solution(s) rotating around them. Your original idea may not be the best.

2. Who else has that problem?

Have your startup team brainstorm all potential customers. Who can use this idea or technology? Map all your ideas, without restriction. The more specific, the better.

Selecting broad market segments will render them meaningless. ‘Consumers’ is not a relevant market segment. ‘24–30-year-old male, who is online and makes over $75K per year and lives in an urban environment’, on the other hand, tells you something very specific about your customer.

For example, this is too broad of a description for a target audience for an AI-based restaurant recommendation app that uses cryptocurrencies:

Men & women over 25 years old who are interested in food + cryptocurrency users/cryptocurrency community

3. Who are you going after first?

Now comes an analysis of each identified market segment, based on a few key elements:

- Are there enough potential customers in that segment to render it viable?

- Are they willing to buy your solution?

- Is the pain they’re experiencing a real pain (or just a minor discomfort)?

- Can they afford your solution?

- Are they easily reachable?

- Can they spread the word to others like them?

It’s here where the pain of narrowing down and the fear of focusing on the wrong segment starts to creep in. Don’t let startup founders fall into this trap. Chasing too many segments or choosing the wrong one is the real risk. Identifying the right one, on the other hand, will guide the development of a product these potential customers will actually buy and use.

4. Building an end user profile

Here’s where we try to go into as much detail as possible regarding who the potential customer is. To do that, we’ll be creating a semi-fictional profile of the ideal customer based on real customer data and educated speculation. The purpose of this profile is to understand the customer demographics, behavior patterns, motivations, and goals that will drive these people to choose your solution. The goal is not to have a list of job titles or specific people, but to identify common behavior patterns, shared pain points, goals, and challenges that potential customers have. Every decision regarding product development, sales, and marketing or business development should tie back to this profile.

The first step is creating a list of questions you want the profile to answer. The more industry-specific the questions, the better the profile. For the purpose of this exercise, we’ll be looking at some key, general questions which can be tailored for each specific industry segment.

Demographics

- What is their gender?

- What is their age range?

- What is their income range?

- What is their geographic location?

- What is their level of education?

- What work experience do they have?

While this is some of the easiest information to obtain, it’s not relevant on its own. This quantitative overview is just a small part of who the buyer persona is.

Psychographics

- What motivates them?

- What do they fear most?

- What are their values?

- What are their goals?

- What frustrates them?

- Where do they go on vacation?

These psychological variables will give you a qualitative description of the end user. The focus here should be on the motives behind behaviors. If you’re working with a startup developing a meal scheduling and preparation app, questions like ‘How many meals a day do they have?’ or ‘How much do they spend on takeout’ will be relevant here.

Proxy products

- What products are they currently buying?

You’ll recognize this question from the problem definition framework. This time, you’re researching your ideal customer more in-depth. The solutions that the end user is using to address the problem you’re trying to solve will help you understand their motives and behaviors better.

- What attributes are they looking for in these products?

- Why these products and not others?

- How are they choosing them?

- How much are they willing to spend for them?

Watering holes

- Where do they get their information?

- What websites/newspapers/apps do they use to stay informed?

- Do they watch TV? What channels?

- Do they listen to the radio? What stations?

- Do they listen to podcasts? Which ones?

- What events do they attend?

Watering holes are the channels or places where your potential customers congregate and exchange information. Both proxy products and watering holes are great for corroborating your demographics and psychographics. If you’re a B2B marketing agency, you’ll probably want to know what type of content they consume or what keywords they use when researching their problem.

How to create a Persona?

A persona is a real person, that matches you end user profile to the extent you can call that person up every time you need to learn more about your end users. Creating a profile means defining all the attributes identified in the end user profile step and enhancing with additional “soft” information.

A day in the life

Think of this as a shadowing experiment, where you try to come as close as possible to live a day in your user's shoes. This day will be composed of multiple people’s experiences. The resulting story will help you piece together all your existing information.

A list of facts won’t be as helpful as a story that draws connections and emphasizes why people behave the way they do. Weave those facts into a story that paints a relatable picture of who your persona is. Keep it fictional, but still realistic.

Biggest fears and motivators

You might feel like you’ve already done this in the Psychographics. This time, you want to prioritize those fears and motivators to find out what keeps your persona awake at night and what makes them get up in the morning. Their top drivers, if you will. This will help you as a prioritization criterion when deciding what features to keep or what marketing strategy to adopt.

For example, meet Sean, 45 years old, from Boulder, CO, USA, works as an investor:

Sean is originally from Denver, studied Telecommunications in Raleigh, at UNC-Chapel Hill, then relocated to San Francisco with a colleague. During an internship at AT&T, they started working on a new protocol for mobile data transfer and later formed a startup around it. One of the AT&T managers put in the initial seed money to get them going and also helped them sell the startup to Cisco two years later (just before the dot-com crash). Both Sean and his cofounder made $4M out of the deal. Sean decided to invest, but the timing was not that good and lost half of his investments when the market fell.

During the 2000s, Sean made smaller seed (10-80k) investments which became fruitful in 2011 when the market came back and acquisitions started again. These small exits eventually increased his net worth to $11M. In 2013 he decided to move his family to Boulder, CO to help Brad Feld with some of his ideas, but also for the great lifestyle. After a few months of mentoring for Boomtown Boulder (a local accelerator), he joined Bullfrog Capital, a new seed fund in Boulder focusing on AI & Robotics. He's now helping Bullfrog Capital to open a European office, and he travels to London every 2 months to meet with relevant accelerators, corporations, and universities. He’s always monitoring the progress of his portfolio and having calls when he’s traveling.

Sean values progress, he doesn’t usually have a lot of patience and he believes in the power of networking. As an investor, he is eager to find better investment opportunities, sourcing some good deals in Europe faster and making sure current portfolio companies move faster. At the moment, he’s feeling reluctant to invest in early-stage startups in new territories. He struggles when interacting with founders who are not pragmatic or try to oversell him on their ideas and prefers to meet face-to-face, even after investing in a new venture.

Researching your Persona

The (hopefully pre-existing) primary market research is a good starting point. However, to build an accurate representation of your persona, you’ll need to do additional primary market research. What started out as ‘24–30-year-old male, who is online and makes over $75K per year and lives in an urban environment’ needs to become a detailed profile answering all the questions I’ve listed before. If you’ve done a thorough job researching your primary market this step will take less.

I know from personal experience how tempting it can be to skip over or rush through this step because you’re eager to finally develop the tech and change the world. With the risk of sounding like a broken record: don’t do it. Take the necessary time to do it properly and I promise it will help you create a better product. Most businesses create more than one persona. However, I recommend you focus on your primary persona first.

1. Interview your existing customers

If you already have customers, this is your starting point. Who better to help you understand your target market than the people who chose to become your customer? Start with qualitative interviews where you get as much information as possible to answer the questions you’ve set. Compile and transform these notes into a complete personal profile that aggregates data from all customers.

2. Use educated assumptions

If you don’t have any customers yet, try to find people in your market segment. You can do this online, by searching for questions they’re asking on search engines, social networks or on key industry blogs and publications. Use keywords and content tools to figure out as many answers to your questions as you can. Ideally, you should also try to meet these people in real-life at conferences or events, or through your network of friends and connections to validate the answers you’ve found.

3. Find more people

One of the most common questions I get regarding personas is ‘How many people do you need to talk to?’ There’s no perfect number. Talk to as many as it takes to start to discover patterns in their answers.

Always circle back the persona

The exercise in itself doesn’t seem too difficult for most founders. The truly difficult part is keeping this persona top-of-mind.

I can’t tell you how many startups I’ve seen do their market segmentation, create their personas and then go back to chasing five different industries. With so many things happening at once, it’s easy to get sidetracked and cave to that fear of missing out.

There are also cases when startups begin to sell to an entirely different segment than the one they used to map their persona just because it was easier to sell there. In cases like these, it’s obvious that they choose the wrong persona to start with. It may also be that it is easier to sell to your group of friends, but once you get out you realize similar people do not really want/need the product. The most likely scenario is that their initial profiling was just building on their existing bias of who they thought they want to sell to. Good research is the only way to avoid that from happening.

Finally, keep in mind that your persona is constantly evolving. Every couple of months or so you should be updating it with new information you’ve learned about your prospects and customers so that it stays a relevant beacon for your business to focus on.

The Problem Statement Canvas for Startups and Innovation Teams

The number one cause of startup failure is the lack of a real need in the market, according to a recent post-mortem on startups. This reminded me of probably the most important lesson I’ve learned from my mentor and friend Bill Aulet, Managing Director of the Martin Trust Center for MIT Entrepreneurship, a professor at the MIT Sloan School of Management, and author of the Disciplined Entrepreneurship books:

“The single necessary and sufficient condition for a startup to succeed is a paying customer”

—Bill Aulet, MIT

I’ve worked with Bill for the past few years, helping to spread the Disciplined Entrepreneurship approach, also teaching and coaching teams at the MIT Global Entrepreneurship Bootcamp, MIT Enterprise Forum, Singularity University, Future Innovators Summit, and many other acceleration programs around the world. During all these years, I saw a recurring pattern among startup founders, which is their obsession with the solution. They are so driven by their vision of a better technology, that they forget the most important things about startups, which I annoyingly remind to every founder I talk to (including myself):

A startup is a business, not a product.

Most of these founders are passionate engineers, designers or business people who want to build amazing things—apps, platforms, robots and more. They end up sacrificing their job, their lifestyle and sometimes their personal relationships for this passion and their vision. At the same time, this is also one of the main reasons they fail.

The hunt for unicorns driven by Silicon Valley investors requires entrepreneurs to be delusional, considering that there are only 174 unicorns (startups valued at over $1B) in the US. It is a mindset that encourages the ‘can’t-possibly-fail’ startup syndrome, an unfortunate wishful thinking on the part of many brilliant startup founders. Eventually, they build great technology but fail to identify the right problem and end up joining the startup graveyard.

As a startup founder, investor, accelerator manager, or mentor you want to do everything you can to mitigate these failure rates and the one way to achieve that is by obsessively focusing on the problem in the early stages, instead of the technology. The real talent in all entrepreneurship—not only in tech startups—is finding the right problem, not building the right solution. In other words, it is vital to have the skills of Sherlock Holmes, not only those of Doc Brown. Once the problem is correctly identified and understood, building the right solution that will lead to a good business is much easier.

The problem statement canvas

Let me walk you through the process of defining problems using a problem pitched by one of the startups I’ve recently mentored:

“People have a huge problem with traffic in São Paulo. We’re going to build the leading ridesharing app for them.”

It was a good start, but the “problem” with this problem statement is that half of it talks about the solution. I could not really understand who those people were, how huge the problem was, and could not be convinced by yet another “app” solution for a systemic problem. Truly identifying a problem means looking deeper at the symptoms, the customer, the impact, the alternatives, the opportunity, and the relationships between them, while avoiding the “solution bias” (often known as “The problem is that the customer does not use my solution”):

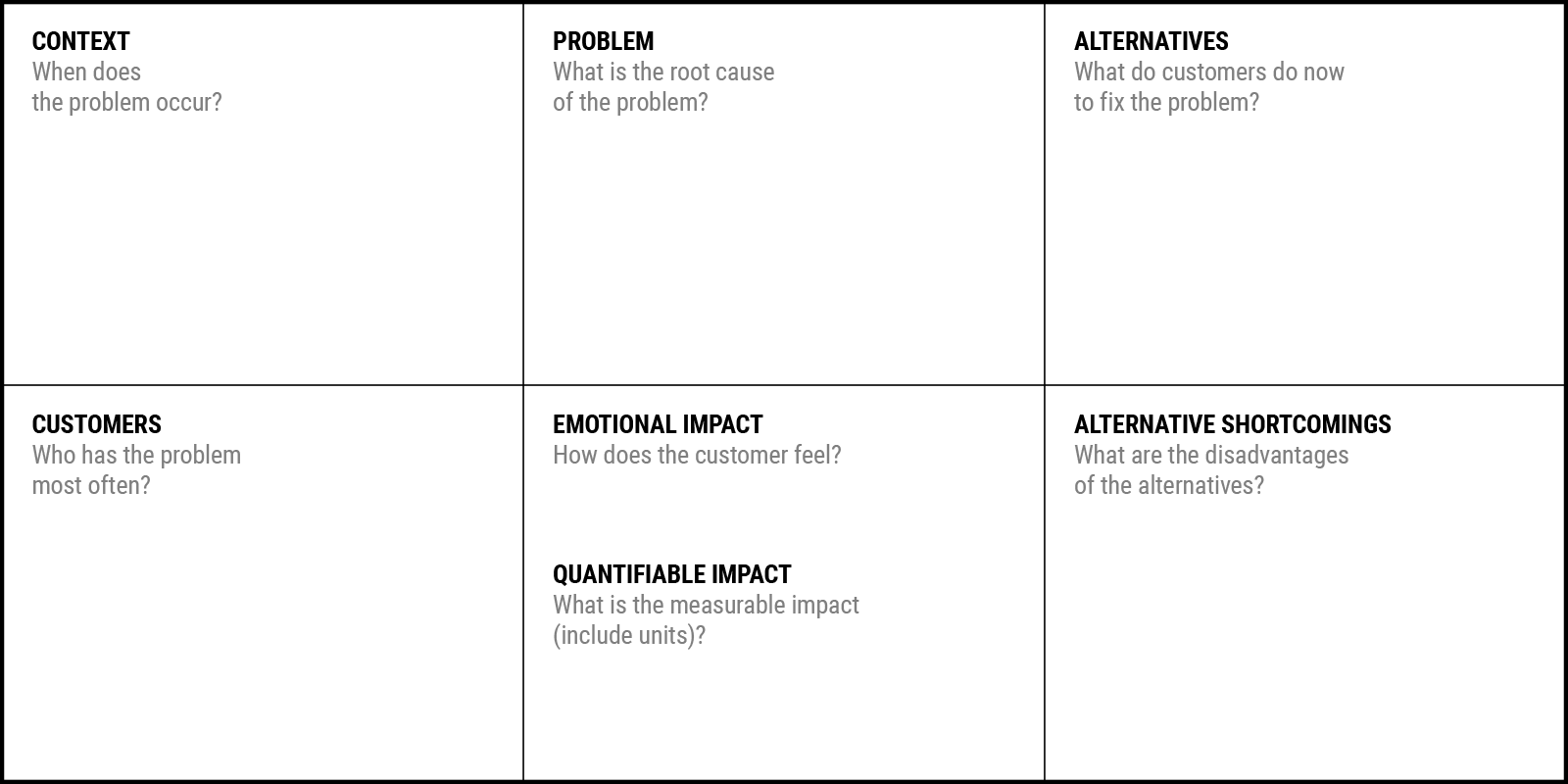

After coaching and mentoring hundreds of startups around the world, learning from some of the best mentors and successful entrepreneurs, I’ve created a simple tool for defining problems in the right way: the Problem Statement Canvas.

While far from being perfect, this way of stating the problem helps everyone better understand the complexity of the problem, completely leaving out the solution. The generic format of the problem statement can be summarized as follows:

When context occurs,

customer type who has characteristic and characteristic,

have problem.

Because of this, they feel emotion, then experience quantifiable impact.

Currently, they use alternative solutions

despite disadvantages.

For those of you who are more visual, the canvas can also be used in a visual format.

Regardless of whether you’re the founder, or you’re working with a startup as an investor or mentor, this is something you want to go over together. Having a common understanding of the problem at each level in the company is critical. Let’s go into each area of the canvas.

Customer type

One of the early stage mistakes is not focusing on the right customer, because of the mirage of keeping multiple opportunities open. “Closing a door on an option is experienced as a loss, and people are willing to pay a price to avoid the emotion of loss,” concluded an experiment ran at MIT by Dan Ariely, a renowned behavioral economist.

You want to focus, and find the 10% of the people for whom the problem is a real pain, not the 90% for whom it’s just a nuisance. Who are they? Where do they live? What is their income? What does their regular day look like? As a founder, you want to be able to walk in their shoes, do their job, live their life, talk to them over breakfast, lunch or dinner, observe them and even ask to shadow them. You want to understand the customer through a demographic and psychographic lens, using at least 2-3 relevant criteria.

To get back to our initial example, instead of:

“People in São Paulo”

we successively refined the customer profile to:

“Young men aged 25–35, with middle-low income, who live in suburban São Paulo and work in a corporate office in the city center.”

Focusing on a single customer segment, which could be your beachhead market, has many benefits:

- You avoid the Chinese glove market fallacy.

- You get an in-depth understanding of how the problem affects people’s lives.

- It’s easier to find those people and discover patterns of behavior, which makes it easier to market the product to them.

- From a business point of view, it’s better to build the best solution for a specific group of customers, than to build yet another average solution for a larger market.

Remember The Social Network movie? Today, everyone imagines that Facebook achieved total world domination by, well, just thinking like a unicorn. But that’s not true. Facebook started as a network for Harvard students, solving student-specific problems. Then, it scaled to other Ivy League colleges. Afterward, it went to other colleges in the US (remember when you could not get a Facebook account unless you had a .edu email address?). Only later on did it open up to everyone, but this strategy helped them focus on what mattered to their customers. They did not start by taking on MySpace or Friendster.

Context

When does the problem occur? Most of the problems are not permanent, and understanding what triggers them will help you further understand the root cause of the problem. More than this, you will understand what is the window of opportunity—when the problem becomes acute and most painful for the customer, and also when he is also most likely to take action (which in the future could be acquiring your solution).

For our startup, the context then became

“Every workday, in the mornings and evenings, for an average of 2-3 hours per day.”

Root problem

Working with the team, we initially came to this refined problem:

“Are stuck in traffic.”

However, this is not the root problem, but rather a complex of symptoms. Identifying the root cause, not the symptoms, is essential to building the right solution. Identifying the root is often difficult, but fortunately, a technique called root cause analysis will help us get to the real issue.

Focusing on events/consequences that exist and asking “why is this a problem?” several times will help you get to the real root cause that you have to address. For example, you might have a problem: your car does not start. But that’s not really a problem, it’s a symptom. You can usually find the first cause of this problem by asking “Why?” The answer is “The battery is dead.” Many entrepreneurs will stop here, then embark on a journey of building better car batteries.

By applying the process we get different answers:

- Second why: The alternator is not functioning.

- Third why: The alternator belt has broken.

- Fourth why: The alternator belt was well beyond its useful service life and not replaced.

- Fifth why: The vehicle was not maintained according to the recommended service schedule. (the root cause).

Do you still think that building better car batteries is a viable solution in this case? Or rather coming up with a different solution that solves the servicing schedule?

We applied the above thought process for our team:

- First why: Because it takes a long time to get to work

- Second why: Because they are wasting precious time

- Third why: Because they might use that time to do something more valuable

- Fourth why: Because they could earn more money in that time

So the final problem could be stated as:

“Could do something more valuable in the time they lose in traffic.”

Emotional impact

It’s not enough to understand the problem as a phenomenon or as an event; you also have to consider its emotional impact, because this helps you walk in your customer shoes and understand their behavior. Each problem causes an emotional response (joy, sadness, anger, fear, trust, distrust, surprise, anticipation) and its magnitude is directly linked to the person’s interest in using your solution. If someone is merely annoyed by something, they are much less likely to try a solution than if they were angry when the problem occurred.

Fully understanding these emotions is essential in identifying windows of opportunity and triggers that will make your customers use your solution. “When customers are in homeostasis their habits are set and you’re not going to move them,” says Bill Aulet in the Disciplined Entrepreneurship Workbook, who has analyzed recent insights from behavioral economics, in order to identify when a startup has a greatly increased chance of influencing customer decisions and to understand what triggers the use (and then the purchase) of a new solution.

In our above case, the emotions are frustration and boredom.

Quantifiable impact

At a certain stage, a startup has to determine its pricing strategy. For this, it needs to quantify its value proposition which is difficult without understanding and quantifying the impact in the current state.

The impact should always be expressed in a currency. These currencies can be more legible (money, goods, time) or less legible (energy, health, relationships). Ideally, you would want to express the impact in a currency that is as legible as possible, because the impact is more visible in loss of cash, goods or time than the loss of relationships or health. This will also help to communicate it more convincingly to the customer.

In our case, we identified the impact as being:

“Lose on average 40 hours per month.”

Alternative solutions

For many disciplined founders, the work stops with the previous step. But before jumping to a solution, shouldn’t you look at what your potential customers are doing to treat their pain or some of its symptoms? If what you discovered to be a problem is really a problem, your customers are likely to be using different tools and actions, or combinations of them, to ease or manage the pain.

Sometimes they might be improvising ingenious things to fulfill their needs, something that MIT professor Eric von Hippel describes in his Free Innovation book. Looking at these alternative solutions and breaking down each of them into pros and cons, will be a great help in identifying opportunities for a painkiller solution.

Flipboard, for example, looked at the success of read-it-later tools like Instapaper or Pocket which allowed users to read interesting articles without the clutter of their web pages. They took the time to understand how users were reading traditional paper-printed magazines, before creating a great reading experience with their iPad apps. Eight years later, it’s still one of the top News apps in both App Store and Google Play.

Slack did not reinvent the wheel, they just looked at what people were already doing by using email and group messaging tools like ICQ or IRC chats to improve their productivity, and made a rather simple tool that better enabled those behaviors in a work context.

Our São Paulo startup identified a few behaviors of which one later became a critical element of formulating their solution:

“They sign up for Uber but only accept rides when they go to work or come back.”

Alternative solution disadvantages

Competition is good, it proves the problem is real. But what if you can’t beat the competition (which is the case in many mature markets)? That’s the reason why finding the disadvantages or shortcomings of alternative solutions will help you understand where the core of your solution (your unfair advantage) resides.

For our team it was easy:

“Driving for Uber requires you to spend more time waiting for a ride in the area, as the origin and destination of the trip might not coincide with your home-work itinerary.”

Taking a step back

At this stage, we can look at the initial statement, which rather sees the systemic size of a problem (very hard to solve):

“People have a huge problem with traffic in São Paulo. We’re going to build the leading ridesharing app for them.”

Then compare it with the one we came up with after going through this process:

Every workday, in the mornings and evenings (for an average of 2-3 hours per day),

young men aged 25–35, with middle-low income, who live in suburban São Paulo and work in a corporate office in the city center

lose time in traffic instead of doing something more valuable with it.

This makes them feel frustrated or bored,

as they lose on average 40 hours per month.Currently, they might sign up for Uber and accept rides when they go to work or come back.

However, driving for Uber requires them to spend more time waiting for a ride in the area, as the origin and destination of the trip might not coincide with their home-work itinerary.

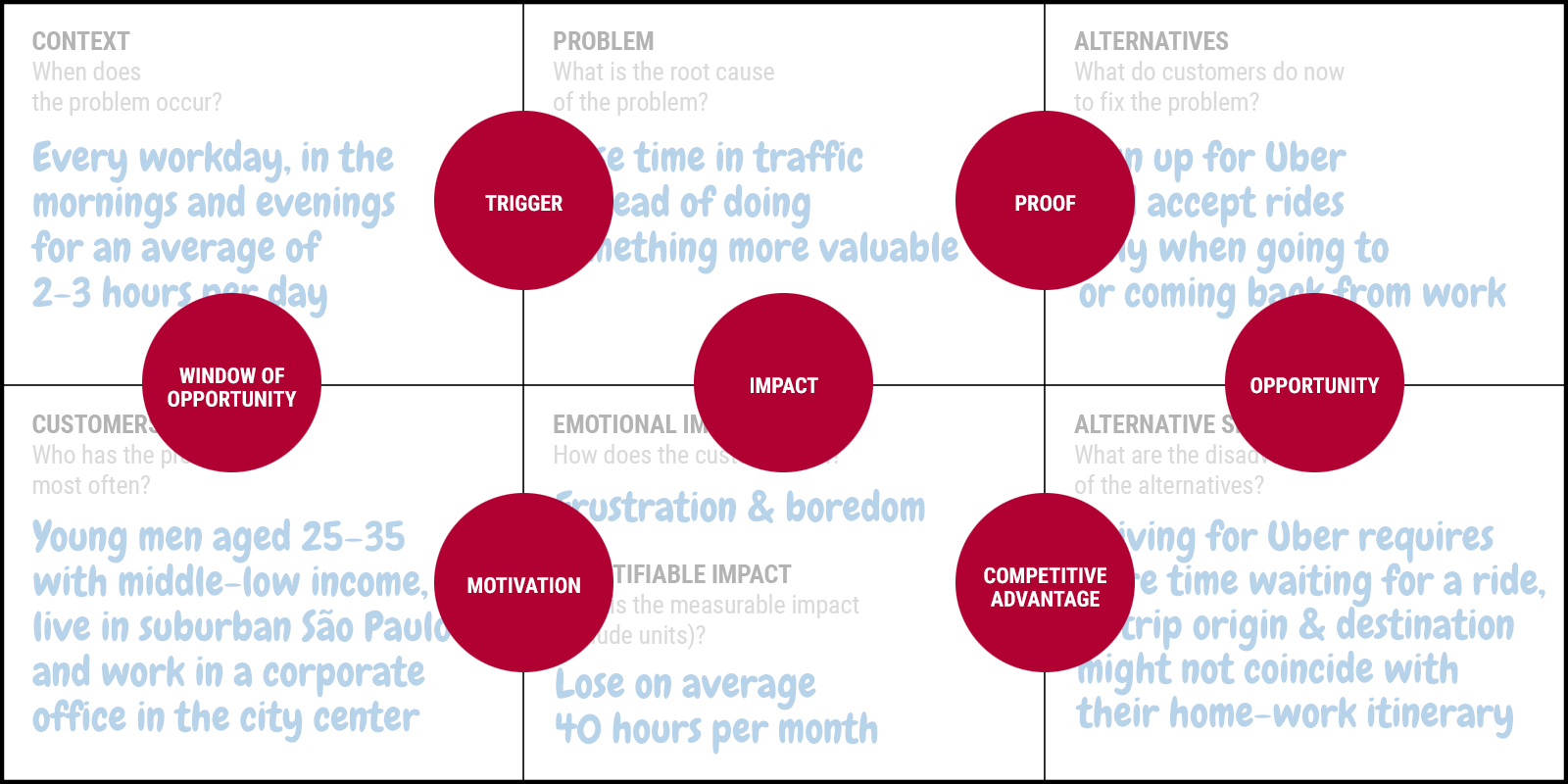

Or in the visual problem statement canvas:

What’s even more interesting is that at the intersection of the above areas we will discover some key elements for turning the problem into a viable solution and business, as you can see in the canvas below:

This process led the São Paulo team to come up with a rather different solution than the initial one they imagined, one which would have been hard to identify without looking at all the above. The solution was a ride-sharing platform that allowed their customers to generate revenue while driving other people in their neighborhood to work. Unlike Uber, their solution was subscription-based and a very ingenious way of generating not only revenue but also quick growth.

Maybe, in a few years, this will even solve the systemic traffic problem in São Paulo. But until then, their startup has the change of becoming a profitable business that generates true value for their customer.